ABCDE (Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure) Approach

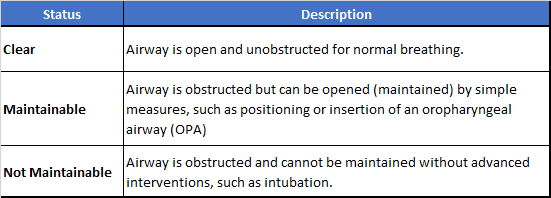

AIRWAY ASSESSMENTAssess the airway to determine whether it is open and clear or obstructed.

Evaluate the following:

Look for movement of the chest or abdomen

Listen for bilateral breath sounds and air movement

Feel for movement of air at the nose and mouth

If there is some airway obstruction, you then decide if the airway is maintainable or not maintainable.

If you think that the airway is obstructed, you must decide where the obstruction is located. The obstruction may be in the upper airway.

Signs that suggest the upper airway is obstructed are:

Increased inspiratory effort with retractions

Abnormal inspiratory sounds (snoring or high-pitched stridor)

Decreased air movement despite increased respiratory effort

If the upper airway is obstructed, try to maintain an open airway with simple measures. if you cannot maintain the airway with simple measures, get help for advanced treatment.

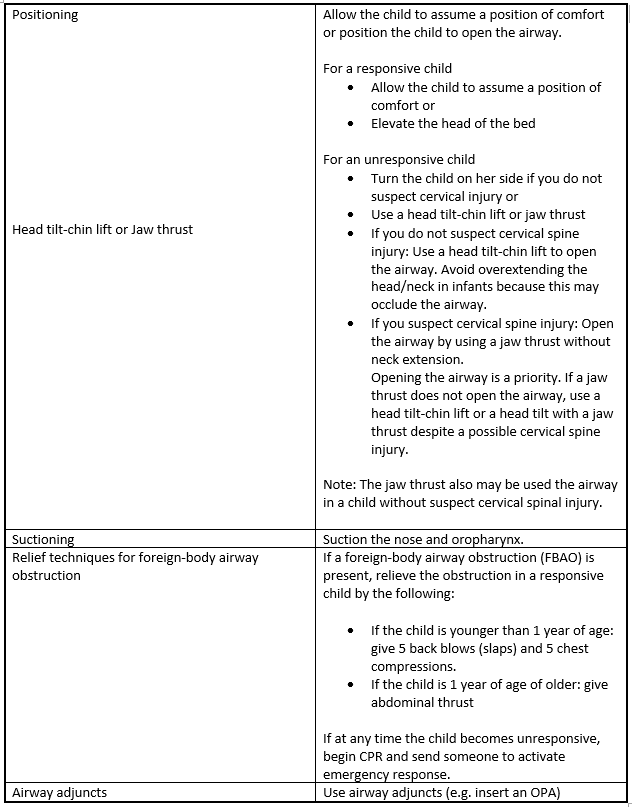

Simple Measures to Maintain the Airway

BREATHING ASSESSMENTDuring the immediate assessment of breathing, it is vital to diagnose and treat immediately life-threatening conditions (e.g. acute severe asthma, pulmonary oedema, tension pneumothorax, and massive hemothorax).

Assess breathing by evaluating:Respiratory rate and pattern

Respiratory effort

Chest expansion and air movement

Lung and airway sounds

Oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry

Normal Respiratory Rate and Pattern:Normal Breathing takes little work: breathing is quiet, with unlabored inspiration and passive expiration. The child looks comfortable. The normal respiratory rate is typically faster in younger infants and children than in older children. Try to evaluate the respiratory rate before you touch the child. If the child becomes anxious or upset, the respiratory rate will often increase.

To determine the respiratory rate, count the number of times the chest rises in 30 seconds and multiply by 2. Be aware that normal sleeping infants may have irregular breathing with pauses lasting up to 10 or even 15 seconds. If you count chest rises for less than 30 seconds, you may not estimate the rate accurately. Count the respiratory rate several times as you assess and reassess the child to detect changes. Many cardiac monitors also have the ability to continuously monitor the respiratory rate.

A consistent respiratory rate of less than 10 breaths/min or more than 60 breaths/min in a child of any age is abnormal. Such a slow or rapid respiratory rate suggests a serious condition and requires immediate intervention.

Detailed and Advanced Concepts:

Be careful to consider the child's clinical condition when you evaluate the respiratory rate and pattern.

An increase in respiratory rate may be appropriate if the child has a fever or if the child is ill or in pain.

A decrease in respiratory rate from fast to "normal" may include overall improvement. Improvement should be accompanied by an increased level of consciousness. The child who is improving should also shoe decreased work of breathing.

A decreasing respiratory rate or irregular respiratory pattern may also indicate that the child's clinical condition is worsening. The child's general appearance or signs of circulation will often change as the child's condition worsens. Skin color may become pale, mottled, or cyanotic. The child's level of consciousness may decrease.

Abnormal Respiratory Rate and Pattern:Irregular respiratory pattern

Fast respiratory rate

Slow respiratory rate

Apnea

1. Irregular Respiratory Pattern

Children with neurologic problems may have irregular respiratory patterns. Examples of such irregular patterns are

A deep gasping breath, followed by a period of breath holding

A rapid respiratory rate, followed by periods of apnea or very shallow breaths

Irregular patterns such as these are serious and require urgent evaluation.

2. Fast Respiratory Rate

A fast respiratory rate (tachycardia) is a breathing rate that is faster than normal for age. This is often the first sign of respiratory distress in infants. Tachycardia can also develop during periods of stress.

A fast respiratory rate may or may not be accompanied by signs of increased respiratory effort. A fast respiratory without signs of increased respiratory effort may result from:

Conditions that do not involve the respiratory system, such as high fever, pain, and sepsis (serious infection)

Dehydration

3. Slow Respiratory Rate

A slower than normal respiratory rate may be caused by:

Fatigue

A central nervous system injury or problem that affects the respiratory control center

Very low blood oxygen concentration (i.e., low oxygen saturation, indicated by pulse oximetry or cyanosis)

Sepsis

Hypothermia

Drugs that depress the respiratory drive

Some muscle diseases that cause muscle weakness

4. Apnea

Apnea is a pause in breathing for at least 20 seconds. Apnea is also present if the pause is less than 20 seconds and other signs of inadequate breathing are present. Other signs of inadequate breathing can include slow heart rate, cyanosis, or pallor.

Detailed and Advance Concepts:

A slow respiratory rate or an irregular respiratory rate in a severely ill or injured infant or child is a sign of a serious problem. It often signals that the child may soon develop respiratory arrest. If you encounter such a child, immediately activate emergency response and be prepared to provide rescue breathing.

Increased Respiratory EffortEvaluate respiratory effort to assess the severity of the child's condition and the need for urgent intervention. The following are signs of increased respiratory effort:

Nasal Flaring

Retractions

Head bobbing or seesaw respirations

Grunting

The child who has increased respiratory effort is trying to improve the level of oxygen in the body (oxygenation) or is trying to improve carbon dioxide elimination (ventilation) or both.

1. Nasal Flaring

Nasal flaring is a widening of the nostrils during each inspiration. The nostrils open to maximize airflow during breathing. Nasal flaring is most commonly seen in infants and younger children. It is usually a sign of respiratory distress.

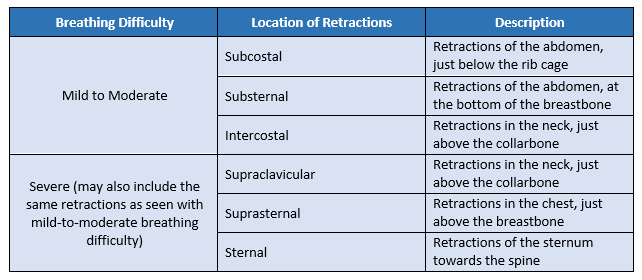

2. Retractions

Retractions are an inward movement of the chest wall, neck, or sternum during inspiration. Retractions may occur in several areas of the chest, as noted in the table below. In more severe cases, retractions may be present in all of these areas.

Retractions are a sign of increased respiratory effort. The child is using chest muscles to try to move air into the lungs. However, air movement is impaired by narrowing of the airways or by stiff lungs. the severity of the retractions generally corresponds to the severity of respiratory distress.

The following table describes the location of retractions commonly seen with each level of breathing difficulty:

3. Head Bobbing or Seesaw Respirations

Head bobbing and Seesaw respirations are signs of severe respiratory distress. These signs often suggest that the child's condition may worsen. If you see these signs, you should get help.

Head bobbing is caused by the use of neck muscles to assist breathing. During inspiration the child lifts his chin and extends his neck. During expiration his chin falls forward. Head bobbing is most frequently seen in infants.

Seesaw respirations are distinct form of "abdominal breathing." During inspiration the chests retracts inward, and the abdomen expands. During expiration the chest expands, and the abdomen moves inward. Note that normal infants can have abdominal breathing., with the abdomen rising during inspiration. With normal abdominal breathing, no other signs of increased respiratory effort are present.

Chest Expansion and Air MovementTo assess chest expansion and air movement, you should:

Observe chest wall movement

Listen for air movement with a stethoscope

1. Chest Expansion

Chest expansion (chest rise) during inspiration should be equal (symmetrical) on both sides of the chest. Expansion may be subtle during spontaneous quiet breathing when the chest is covered by clothing. But chest expansion should be easy to see when the chest is uncovered. In normal infants the abdomen may move more than the chest during inspiration.

Some causes of decreased or unequal chest expansion are:

Inadequate effort

Airway obstruction (narrowing of the small airways or presence of secretions in the larger airways)

Aspiration of a foreign body

Collapse of all or part of the lungs

Air, blood, or fluid in the space surrounding the lungs

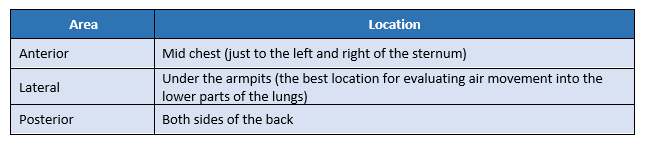

2. Air Movement

Note the quality of air movement. Because the child's chest wall is thin, it is easy to hear air movement or airway sounds in one part of the chest when your stethoscope is over another part of the chest. You may also hear sounds from the upper airway when you listen all over the chest. This is because sound is easily transmitted through the chest from the upper airway.

Listen to the loudness of the air movement:

Normal inspiratory sounds should be soft and quiet. Watch the movement of the child's chest as the child inhales. Inspiratory sounds should occur at the same time as the chest movement.

Normal expiratory breath sounds are often short and even quieter than inspiratory sounds. You may not even hear the sound of normal expiration.

Lung and Airway Sounds1. Stridor

is a coarse, high-pitched sound. It is typically heard during inspiration. Stridor is a sign of upper airway obstruction. It may indicate severe airway obstruction, requiring immediate intervention.

Common Causes:

Croup

Aspiration of a foreign body

Infection

2. Snoring

Although snoring may be common during sleep in children, it also can be a sign of airway obstruction. Soft tissue swelling or decreased level of consciousness may cause airway obstruction and snoring.

3. Barking Cough

A barking cough is another sign of upper airway obstruction that may occur with respiration problems such as croup. The sound results from rapid movement of air though a narrowed upper airway.

4. Hoarseness

Hoarseness is a sign of upper airway obstruction caused by infection or airway swelling. Hoarseness results from swelling of the vocal cords that interferes with normal vocal sounds.

5. Grunting

Grunting is a short, low-pitched sound heard during expiration. Grunting can result from PULMONARY CONDITIONS such as PNEUMONIA or CARDIAC CONDITIONS such as CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE.

Grunting is typically a sign of SEVERE RESPIRATORY DISTRESS from lung tissue disease.

6. Gurgling

Gurgling is a bubbling sound heard during inspiration or expiration. It occurs when then upper airway is partially obstructed by secretions, vomit, or blood.

7. Wheezing

Wheezing is a high-pitched or low-pitched whistling or sighing sound heard most often during expiration. This sound indicates lower airway obstruction.

Common causes:

Bronchiolitis

Asthma

8. Crackles

Crackles are also known as rales. These are sharp, crackling sounds heard on inspiration. The sound of crackles can be described as the sound made when you rub your hair together close to your ear.

CIRCULATION ASSESSMENT1. Heart Rate

To determine the heart rate, check the pulse rate, listen to the heart, or view a monitor (ECG monitor or pulse oximeter display).

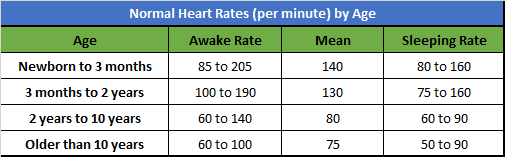

The heart rate should be appropriate for the child's age., level of activity, and clinical condition (Table 1). Note that there is a wide range for normal heart rates.

For example, a child who is sleeping or is athletic may have a heart rate lower than the normal range for age. A child with a fever. especially a high fever, should have a faster heart rate.

Table 1. Normal Heart Rate

Abnormal Heart Rate

An abnormal heart rate is defined as a heart rate that is either too fast (tachycardia) or too slow (bradycardia). It is best to assess the heart rate when the child is resting.

Tachycardia - is a heart rate that is faster than normal for age. A heart rate that is 220 per minute or higher in infants or 180 per minute or higher in children may be one sign of a life-threatening condition.

-

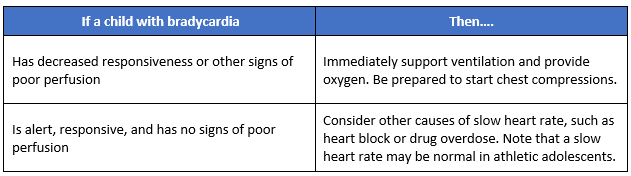

Bradycardia - is a heart rate that is slower than normal for age. when the heart beats too slowly, the heart may not pump enough blood.

Bradycardia may be normal in athletic adolescents, but bradycardia with low blood pressure or poor circulation is never normal. In such cases, bradycardia could indicate that the child may soon develop cardiac arrest.

Severe respiratory distress and inadequate oxygenation of the blood are most common causes od bradycardia in a child.

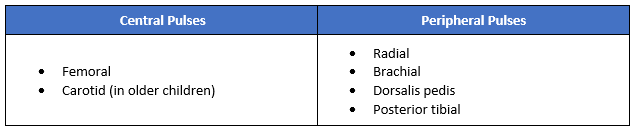

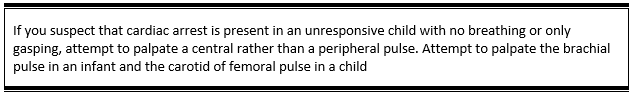

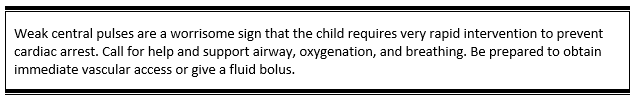

2. Pulses

Evaluation of pulse is an important part of the assessment of circulation.

In healthy infants and children (unless the child is obese or in a cold environment), you should be able to palpate these pulses easily

Central pulses are stronger than peripheral pulses. This is because these blood vessels are larger and closer to the heart.

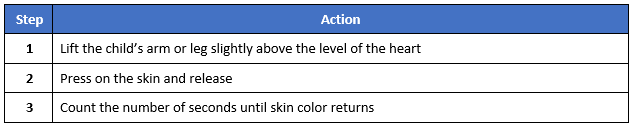

3. Capillary Refill Time

Capillary refill time is the time it takes for blood to return to tissue that has been blanched with pressure. Normal capillary refill time is 2 seconds or less. It reflects circulation to the skin. Abnormalities in capillary refill may indicate problems with cardiac output.

To evaluate the Capillary Refill:

It is best to evaluate capillary refill in an environment that is neither hot nor cold. A cold environment may prolong capillary refill time. Causes of delayed or prolonged capillary refill time (a refill time greater than 2 seconds include:

Dehydration

Shock

Hypothermia

4. Skin Color and Temperature

Consider the temperature of the child's environment when assessing skin color and temperature. If the environment is cool, the child may have cool skin with poor color even though circulation is good. Mottling or pallor with cool skin may be present. Capillary refill may be delayed, particularly in the finger, toes, hands, and feet.

To assess skin temperature, use the back of your hand, which is more sensitive to temperature changes than the palm. Slide the back of your hand up the child's arm or leg to see if there is a point where the skin temperature changes from cool to warm.

Carefully evaluate pallor, mottling, and cyanosis, which may indicate inadequate oxygen delivery to the issues.

Pallor - or paleness, is a lack of normal color in the skin or mucous membranes.

Causes of pallor include:

Decreased blood flow to the skin (can be caused by cold, stress, hypovolemic shock)

Decreased number of red blood cells (anemia)

Decreased skin pigmentation

Mottling - or mottled skin, is an irregular or patchy discoloration of the skin. When mottling is present, some irregular skin areas are pink, whereas others may appear pale or cyanotic. Mottling may occur as a result of

Variations in skin coloring

Cold or cool skin temperature

Shock (e.g., Hypovolemia, septic shock)

Decreased oxygen saturation in the blood (i.e., respiratory problems)

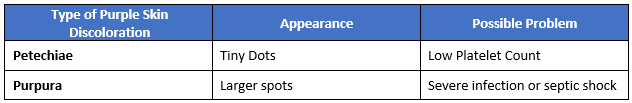

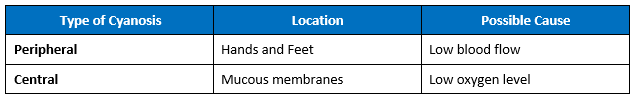

Cyanosis - is a bluish discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes. Cyanosis may be easier to see in the mucous membranes and nail beds, particularly in children with darker skin. It can appear on the feet, nose, and ears.

A child who develops central cyanosis typically needs emergency interventions, such as oxygen and support of ventilation.

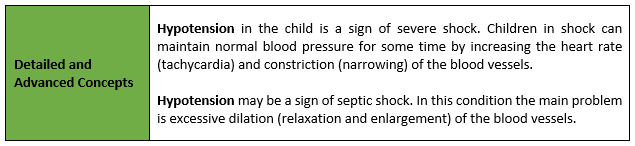

4. Blood Pressure

To measure blood pressure accurately, you must use a properly sized cuff. The cuff bladder should cover about 40% of the circumference of the mid-upper arm. The blood pressure cuff should cover at least 50% to 75% of the length of the upper arm.

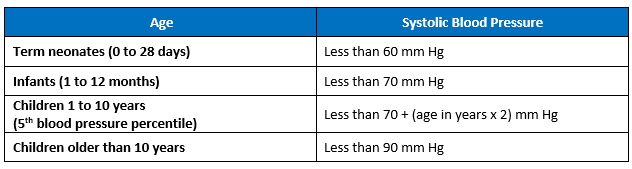

Hypotension - is defined by the following thresholds of systolic blood pressure (Table 3).

Note that these blood pressure values overlap with normal blood pressure values for about 5% of healthy children.

Remember that these threshold values are based on studies of normal, resting children, Children with injury and stress will typically have high blood pressure.

DISABILITY ASSESSMENTThe disability assessment is a quick evaluation of neurologic function. Clinical signs of brain function are important signs of overall blood flow and oxygen delivery. As you form your initial impression and perform the primary assessment, you should note the child's level of consciousness, muscle tone, and pupil response to light.

Seizures may develop if blood flow to the brain suddenly decreases. Monitor the child for the following signs of decreased oxygen delivery to the brain:

Confusion

Irritability

Lethargy

Agitation alternating with lethargy

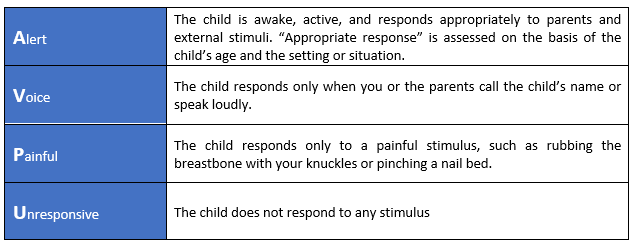

Evaluate disability by using the following:

1. AVPU Pediatric Response Scale

Causes of a decreased level of consciousness in children includes:

Decreased blood flow to the brain (e.g. severe shock or increased ICP)

Infection in the brain (e.g. encephalitis, or meningitis)

Hypoglycemia

Drug overdose

hypoxemia

2. Response of Pupils to Light

During disability assessment, record the following for each eye: using PERRL (Pupils Equal, Round, Reactive to Light)

Size of pupils (diameter in millimeters)

Equality of pupil size (right and left pupils are the same size)

Constriction of pupils to light (i.e., the speed of the pupil response to light and the pupil size when constricted)

3. Blood Glucose Test

You should monitor the blood glucose level of any seriously ill infant or child. Low blood glucose level may cause altered level consciousness and other signs. It can cause brain injury if it is not quickly identified and adequately treated. Measure blood glucose level with a Point-of-care glucose test.

EXPOSURE ASSESSMENTExposure is the final component of the primary assessment. When the child is seriously ill or injured, you should measure the child's core temperature. Identify the presence of fever, which may indicate infection and an early need for antibiotics.

Undress the seriously ill or injured child as necessary to perform a focused physical examination. Remove clothing from one area at a time to carefully observe the child's face, trunk (front and back), extremities, and skin. Keep the child comfortable and warm. If necessary, use blankets and, if available, heating lamps to prevent cold stress or hypothermia.

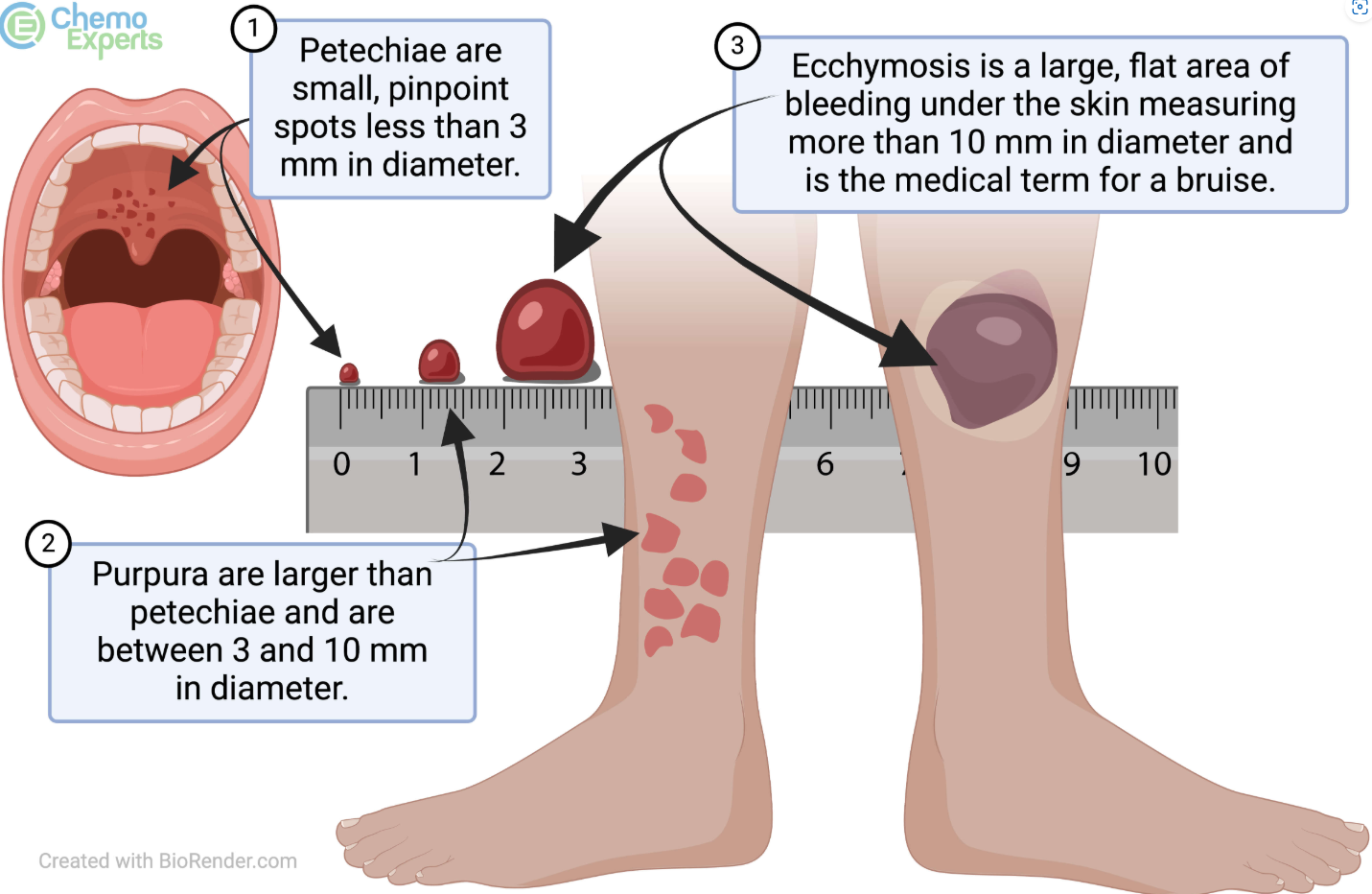

Look for rashes or evidence of trauma. You may see petechiae and purpura, which are purple discolorations in the skin that do not blanch with pressure. They are caused by bleeding from capillaries and small vessels in the skin and often represent a serious or life-threatening problem, such as severe infection, septic shock, or a bleeding problem.